Documentary sources for researching buildings

In NHBG Newsletter No 28 (Autumn 2014), Diane Barr described some of the sources she had found most useful when exploring the documentary history of Walsingham and, in particular, who owned the properties the Group were examining. These are sources that are useful for anyone researching historic buildings. Over the coming months Diane will examine these sources and many more not used for the project. Each piece will describe what the sources are and how to use them, how you access them, their usefulness, and what the pitfalls are in using them.

Building term glossary

PDF of Building terms.

An example:

Sources used in the Walsingham survey

The most valuable historical documents for the study of Little Walsingham were the two surveys or terriers carried out to record the holdings in the tenure of the lord of the manor. A terrier is a written description, usually arranged topographically, of holdings and tenants with their obligations in rent. They are especially useful when they give the names of holdings and their abuttals. This type of survey can be useful for creating maps for a period where no existing map is available for study. The information from these earlier documents was applied to a modified version of the town map surveyed by Charles Burcham in 1812. This map was drawn up for the Great Walsingham, Little Walsingham and Houghton next Walsingham Inclosure Award begun in 1808.

To help strengthen the identification of the buildings surveyed, two sets of minute books were invaluable. One book contained the minutes of the manor of Little Walsingham late Queens, the other of the manor of Granges in Little Walsingham. Both were minutes taken at courts baron held between 1764 and 1848; the court baron was the principal type of manorial court. The main business of the court was to resolve disputes between tenants, and also to record the surrender of and admission to copyhold land held by the manor.

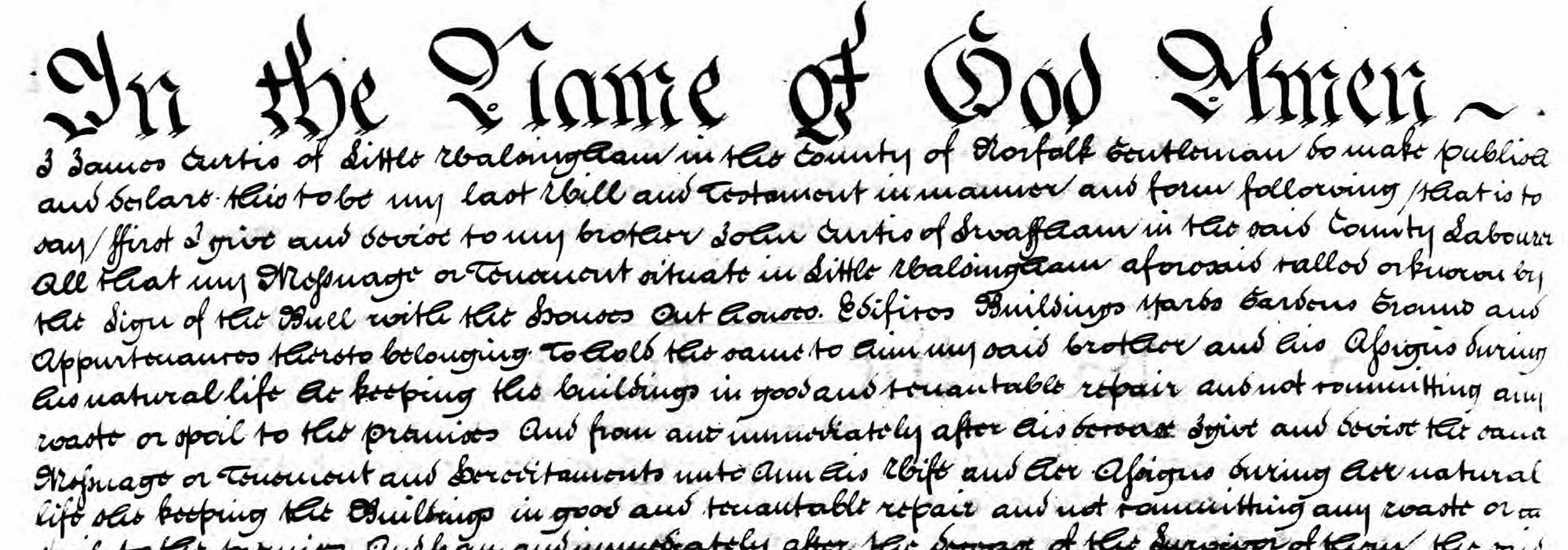

Once the name of an owner had been established, record repositories were search to see if any wills or probate inventories were available. The main source for wills before 1858 is the church court will register; these are large volumes of copied wills prepared by clerks of the court.

On the right is the will of James Curtis 1829 used for the Walsingham project, it clearly shows the name of the premises. (Click on image to view in Lightbox)

Occasionally, a probate inventory assessing the goods of the deceased can survive with the will. These can give a useful guide to the rooms within a property. However, not all were necessarily recorded; a room may have been empty or filled with nothing of value.

The main sources used for nineteenth information were trade directories, and census returns. Much like their modern counterparts, directories list residents and businesses by trade or street by street. They also give a potted history of the parish as an introduction; this can sometimes reveal a piece of information previously unknown to the researcher. Census returns provide standardised information for each household and, therefore, lend themselves to the statistical analysis for social and spatial relationships within a parish.

More information on Documentary sources

1. Tithe Apportionments and Maps

The tithe surveys of the 1830s and 1840s are a good starting point for researching a building that is hundreds of years old. From them the researcher can work backwards and forwards using other documents to build up a history of a property. They can sometimes be the only full record of owners and occupiers in a parish where estate plans and surveys are scarce. A tithe apportionment and map was commissioned for almost all rural parishes in Norfolk between 1836 and 1850.

Tithe apportionments and their corresponding maps are the result of the 1836 government’s decision to commute tithe payments in kind to monetary payments. For many centuries payment of tithes were paid in kind (an agreed proportion of crops, wool or milk produced) by parishioners for the support of their local church and its clergy. This proved difficult to collect and had caused many disputes between farmers and tithe owners. The Tithe Act 1836 set up a Tithe Commission whose role was to administer local agreements made between tithe owners and tithe payers. In parishes where the landowner and the tithe owner were the same person or where tithes had already been commuted into money payments a survey was not necessary. In most cases, the principal record of the commutation of tithes in a parish is the Tithe Apportionment.

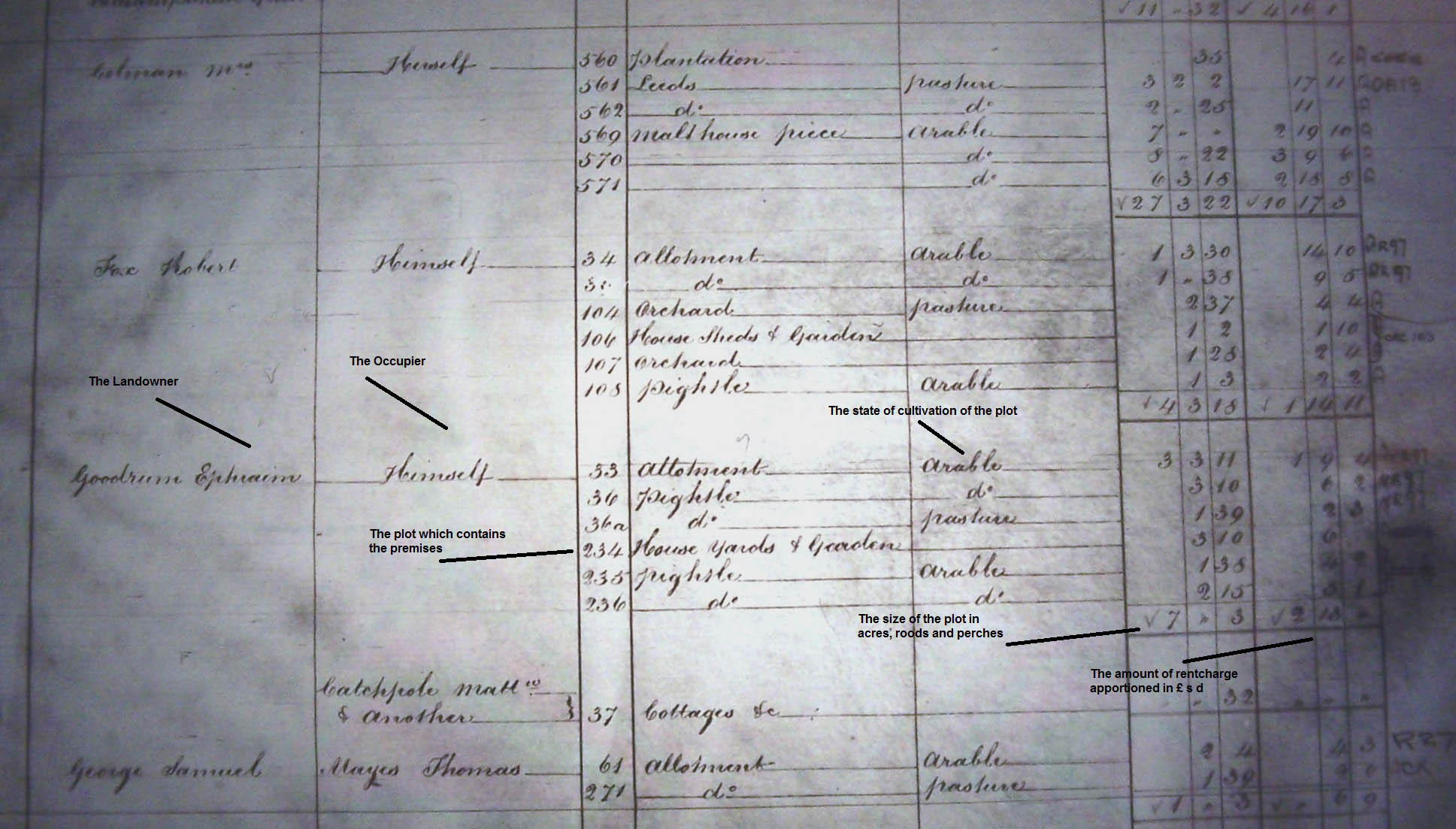

The apportionment opens with a preamble which contains the names of the tithe owners and the circumstances in which they own the tithes. Information is given about the rent-charge agreement or of any compulsory award made by the commissioners. The state of cultivation of land together with areas of common and road systems are also recorded. Most apportionments follow a standard pattern of columns headings:

- the name(s) of the landowner(s) and occupier(s)

- the number, acreage, name or description, and state of cultivation of each tithe area

- the amount of rent-charge payable

- the name(s) of the tithe-owner(s)

The document provides details of landowners and occupiers within each parish, and more significantly for building research a description of each plot or field.

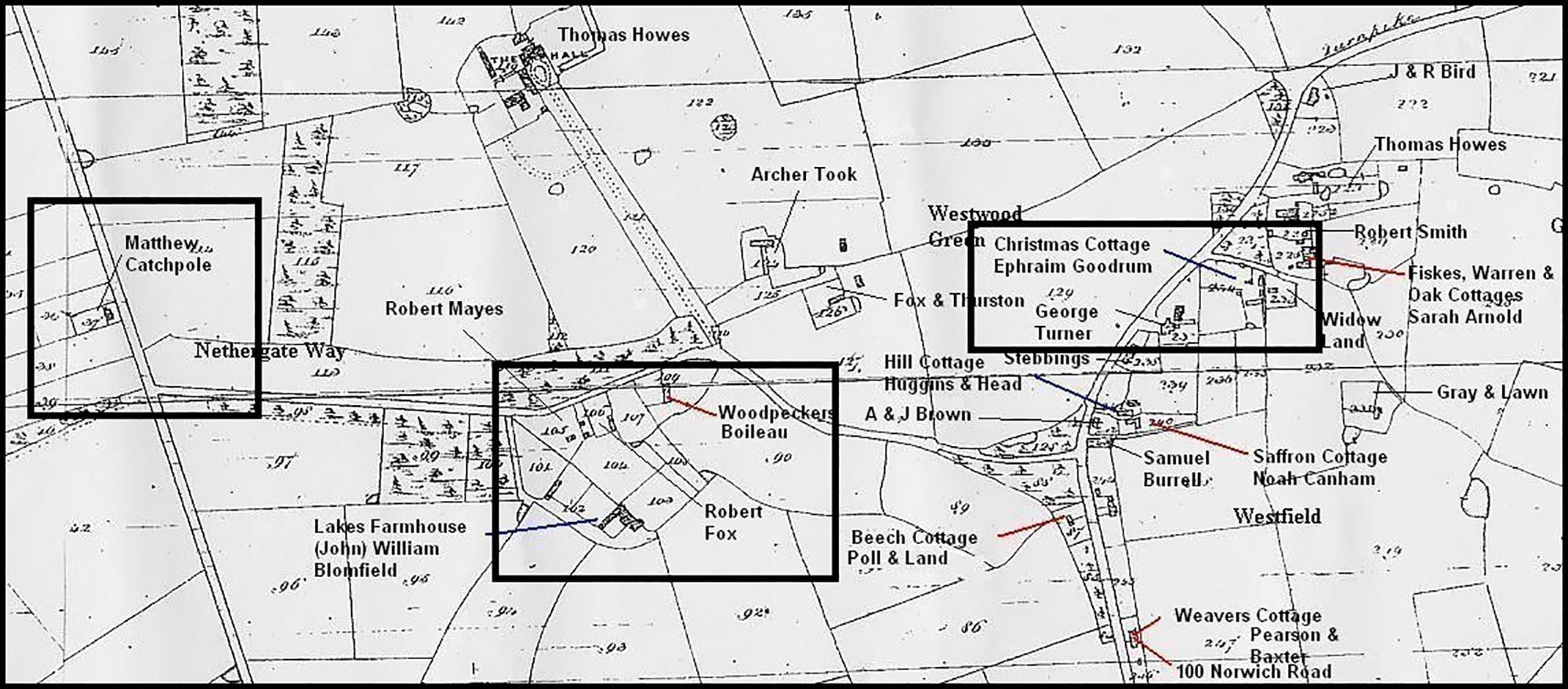

Alongside the description is a reference number that corresponds with a large scale map of the parish showing how land was occupied as well as features such as roads, pond, rivers, woods and churches. Whilst an extant plan of the parish may have been available, in most cases there was no suitable map in existence. Therefore, the expense of any new survey had to be met by the landowners; as a result tithe maps can vary greatly in scale, accuracy and size. However, there are some common features on the maps. Coloured maps usually show inhabited houses in red; uninhabited building such has barns, outbuildings and stables are depicted in black. To make houses more prominent on uncoloured maps the surveyor would shade them in solid black. Roads are generally coloured brown, and water features are outlined or shaded in blue. It is good practice to check the compass drawn on the map as not all maps are orientated with north to the top of the page. The following example is taken from the Tacolneston tithe map dated 1845 (Image upper right, click to open in Lightbox).

Generally, the researcher will know the present day location of the house being researched. Check beforehand that the house is still in the same parish as boundaries can change over time. Once the property has been located on the tithe map it is then a matter of logging the number of the land where the house is situated and then looking up the details on the apportionment. Because properties are listed in alphabetical order of landowners these numbers appear in no clear order. Each property will also have recorded any other plots and fields associated with it. The apportionment will show who the landowner is, they may occupy the property as “him/herself” or it may be occupied by a named tenant. The example below from Tacolneston shows that Ephraim Goodrum has for himself a house, yards and garden, and several pightles. Also he has cottages occupied by Matthew Catchpole and other on plot 37. (Image lower right, click to open in Lightbox).

Make a note of neighbouring properties; these will become useful when tracing the occupiers of your property in other types of record.

As well as being able to use tithe information to find individual occupancy of buildings within a parish, a land occupation survey of the whole parish can be created from the tithe apportionment. It can also provide details of land use, such as arable, pasture, orchards and woodlands for research into changes in farming practice.

Accuracy of information.

Tithe maps should not be seen as an accurate survey of a parish but as record of land on which tithes were paid. The aim was to show the boundaries of all titheable parcels of land; a road may appear because it helps to show the boundary of a plot. If something does not appear on a map, it does not mean that it did not exist: a missing house may mean it was non-titheable. It should be noted that surveys were rarely carried out in urban areas as they were for gathering information about cultivated land.

Where to find tithe apportionments and their maps.

Originally three copies of each tithe apportionment and its map were prepared. One was for the tithe commissioners; these are held centrally at The National Archives in Kew. The other two were made for the diocese and for the parish. For Norfolk, the diocesan copies are held at the Norfolk Record Office at the Archive Centre. These can be view either in their original form or on microfilm. If the parish copy of the tithe survey has survived then it may be also held by the Norfolk Record Office. The Heritage Centre at the Norwich Millennium Library also has copies of the diocesan versions on microfilm. Digitized copies of the maps are available on The Norfolk Historical Map Explorer website http://www.historic-maps.norfolk.gov.uk/tithe.aspx Here nearly 700 tithe maps that cover about 85% of Norfolk can be viewed.

2. Enclosure Awards and Maps

A useful set of records for discovering the history of a property are the documents associated with the Act of Enclosure or Inclosure as it is referred to in a legal context. These records often predate tithe records by 40 years or more making them a useful source for houses built before the survey. Enclosure is the consolidation or extension of land-holdings into larger units by putting a hedge or fence around them. This can include the merging of communally farmed open fields into small fields farmed by individuals, and the occupation of commons by large landowners resulting in the exclusion of other users. The legal documents recording the ownership and distribution of the lands enclosed are called Enclosure Awards.

The history of enclosure spans many centuries and is too complex for the purpose of these articles. Briefly, the enclosure of land developed into three methods:

- Early informal agreements – these are enclosures of common lands, pastures and manorial wastes, made by agreement or by compulsion. They usually have left no formal record.

- Formal non-parliamentary agreement – a document drawn up by a solicitor that gives information about abuttals (a boundary of land with respect to other adjoining lands or roads by which it is bounded) but rarely have a map to illustrate the properties. These can be wordy documents, and it can be difficult to locate your property unless you have an owner’s name with some topographical information already.

- Private Enclosure Acts which lead to public Acts of Parliament – this is when a landowner would get a private Act of Parliament to enclose land in their parish. The Act would appoint commissioners to visit the parish, have it surveyed and to hear the claims of those holding land or rights of access to the common. Private Enclosure Acts became more frequent after 1750 resulting in the passing of public General Acts from 1801.

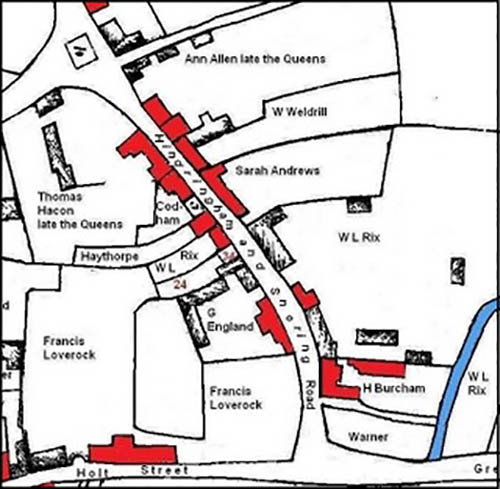

It is these later private enclosures and public acts which provide the best source for the house researcher as they often include a map or plan identifying the owner of a property. Once a survey was completed the commissioners’ decisions were published in the form of an enclosure award with a map showing what is explained in detail in the award.

The award will detail the allocations of land in the new enclosures. The order of the allotments follow the social structure of the parish starting with the lord of the manor (if there is one) followed by the major land owners, and the cottagers recorded last. Each owner’s property will be described and the occupiers listed. Below is a table showing a detail from the Great & Little Walsingham Inclosure Award, 1809. The extract relates to claimants living in Knight Street. Their own residences are highlighted in bold (land allocations are not listed).

| Henry Burcham | Messuage or tenement, buildings, yard and garden | Late Augustine Knocker now untenanted |

| Messuages or tenements, near above with buildings, yard and gardens | Himself, John Burcham, William Yaxley, William Scott Hall, William Doddea and widow Baldwin | |

| 3 Messuage or tenements | Robert Durrent, Thomas Bangy and John Barrett | |

| Elizabeth Codham | Messuage and barn with buildings and yard | Own occupation |

| 4 messuages with buildings and yards | William Lambert, Bridget Utting, John Creed and John Bangy | |

| Messuage or tenement with buildings and yards | Widow Browne | |

| William Loades Rix | Messuage,buildings, yard, garden and plantation | Own occupation |

| Messuage, buildings, yard and garden | Miss Winifred Rix | |

| Cottage with stable, yard and garden, adjoining above | Richard Miller | |

| Two cottages under one roof with buildings, yard and gardens | Edmund Buscall and Elizabeth Scott | |

| Messuage called the Exchange Inn with buildings, yard and garden | Clement Jacob | |

| William Wetdrill | 2 Messuage or tenement,buildings, yard, garden and orchard | Own occupation and Robert Leeder |

| William Haythorpe | Messuage or tenement, buildings, yard and garden | Own occupation |

Besides land and built property ownership enclosure awards and maps detail public and private roads, rights of way, drainage, the ownership of boundaries, and different types of land tenure.

A consequence of enclosure was the necessary changes to public roads, bridleways and paths; these had to be laid first out to accommodate the allocations.

Where a common was being enclosed, a piece would be reserved for the poor to gather fuel called Poor’s Land. The legacy of this can be seen in modern day fuel allotment charities.

As already stated, the enclosure map was drawn up to show what land was affected by the Enclosure Act.

Accuracy of information

There is no set format for the enclosure maps, however they are an accurate survey and can be compared with later maps and aerial photographs. The names written on maps are of landowners who may not necessarily live in the property; the award should list the occupiers. If the owner has more than one built property the researcher will have to compare information gathered from other sources. It is good practice to make a note of owners and occupiers in neighbouring properties as these may be consistent over several sources.

The coverage of each map may vary. Most enclosure maps cover the entire parish but be aware that some only cover the area being enclosed.

Where to find them

Enclosure awards and maps, c. 1750-1850, are held in the Norfolk Record Office at the Archive Centre, County Hall. They do not exist for all parishes and may not cover the whole parish. The record office staff will be able to advise you on whether an enclosure map was produced for a particular area. The Norfolk Heritage Centre at the Norfolk and Norwich Millennium Library also holds a full set of Enclosure Acts running from circa 1770 to the mid-nineteenth century. Digitized copies of the maps are available on The Norfolk Historical Map Explorer website. There are over 100 maps available to view online but the Explorer does not include any enclosure acts or awards.

3. Land Tax Assessments

There is a set of documents a researcher can use to bridge in the gap between the enclosure awards of the early nineteenth century and tithe records of the 1840s. These are Land tax Assessment records which list year by year the names of the owners and the occupiers of land and property in each parish.

Land Tax was introduced in 1692 has a means of raising revenue from personal estate and land to fund the war against France. The tax was finally abolished by the Finance Act 1963. Survival of the tax lists can vary from parish to parish, except for the period 1780 to 1832 when the lists were used to make up the poll books for parliamentary elections. From 1780, payment of land tax on freehold property worth £2 or more a year qualified a man to vote. For this reason, the documents have survived as duplicates among the County Quarter Sessions records. However, from 1832, reform of the voting franchise meant that duplicates no longer had to be collected or retained in Quarter Sessions records.

Early assessments may contain the minimum of information but from 1798 printed forms were introduced; these where gradually taken up by parishes across the country. The forms generally followed the same layout with the following column headings:

1. Name of Proprietor/Owner

Not necessarily the name of the occupier; many owners were non-resident. The term “late” before a person’s name may indicate a recent death, or the sale of the property; the latter reason is useful for indicating a previous owner. Titles such as Reverend, Dr., Sir, Esquire and Mr. (a gentleman) are used to define status.

2. Names of Occupiers

If the occupier is the owner then the term him or herself will be used. Occupiers of a row of cottages may be listed as “John Smith and others”, and tenants of small pieces of land may not be listed individually. First names are not always recorded – names such as “Matthews and others” or “Widow Gibson” may be used.

3. Names or descriptions of estates or property

From around 1825 this useful column was introduced. Terms such as “house and garden”, “messuage and land” or “cottages” are used to help distinguish buildings from land.

4. Sums assessed and not exonerated/exonerated

This is the amount of tax charged. This gives an idea of the size and value of the property; cottages and gardens are obviously taxed at smaller amounts than farms and estates.

How to approach tax assessments

Firstly, the researcher will need to determine in which division or hundred their parish sits as the records for Norfolk are preserved amongst the Norfolk Quarter Sessions records. Staff at the archive will be able to assist with locating your parish. Although the original returns may be available for viewing, copies of them are kept on microfiche; this is the best way to view them.

Having established who owns and occupies the property in the tithe survey it is best to start at the assessment for 1832 and work backwards. This way means you have the useful description column to confirm it is a building and not land. The researcher should persist in working through the returns for each year as the properties are generally laid out in the same order. Make note of the name of owner, name of occupier, the description of the property (if listed) and its rental or tax rate. The example below for Tacolneston from 1797 and 1832 illustrates the value of the rental has changed little over the run. The exception being the rent value 18 for Revd. J Warren which has been sub-divided between John Blomfield and Daniel Turner: note the entry stays in its customary position on the list

|

1797

|

1832

|

||||

|

Rental

|

Owner

|

Occupier

|

Rental

|

Owner

|

Occupier

|

|

61.1

|

Revd. Charles Browne

|

John Browne

|

61.1

|

John Graver Browne

|

Robert Knights

|

|

6

|

Revd. Charles Browne

|

John Nichols

|

6

|

John Grave Browne

|

Edward Huggins

|

|

5

|

Revd. Charles Browne

|

Thomas Huggins

|

5

|

John Grave Browne

|

Ann Church

|

|

24

|

Late Rant Esq

|

? Muskett

|

24

|

John Graver Browne

|

John Blomfield

|

|

2

|

Late Rant Esq

|

Robert Ragg

|

2

|

John Graver Browne

|

Robert Ragg

|

|

18

|

Revd. J Warren

|

Thomas Mayes

|

16

|

John Blomfield

|

James Blomfield

|

|

2

|

Daniel Turner

|

Self

|

|||

|

5.1

|

James Spinks

|

Himself

|

5.1

|

William Blomfield

|

James Blomfield

|

|

15.1

|

Rector Riburgh

|

James Blomfield

|

15.1

|

Revd. Clayton

|

William Howes

|

|

5.1

|

Archer Browne

|

Himself

|

5.1

|

Simon Browne

|

Himself

|

|

1

|

Lucy Browne

|

Herself

|

1

|

George Turner

|

Self

|

|

3

|

John Howard

|

Robert Mayes

|

3

|

Ephraim Goodrum

|

Self

|

|

1

|

Widow Browne

|

Widow Boldero

|

1

|

William George

|

Canham & Tooke

|

If an owner holds a group of properties, details of all of them should be recorded as they may be lumped together under one owner’s name with one tax assessment in earlier returns. The sums assessed for the individual properties should add up to the total making it possible to see if the house is still included.

If we systematically record the land tax returns for the property owned by Ephraim Goodrum (green) used in the tithe apportionment example, we can make an assumption for owners and occupiers back to 1797:

| Year | Owner | Occupier |

|---|---|---|

| 1822/45 | Ephraim Goodrum | Himself |

| 1818/21 | Samuel Stebbins | Robert Fox |

| 1817 | Smith | Stebbins |

| 1816 | Lucy Browne | Stebbins |

| 1814 | Lucy Browne | Thomas Browne |

| 1809/11 | Thomas Browne | Himself |

| 1797/1807 | John Howard | Robert Mayes |

Problems with tax assessment records

- Difficulties in tracing a property does arise if there has been a change of owner in the period between the tithe survey and land tax, however, the occupier may have remained the same.

- Owners and occupiers could hold land in more than one parish and did not always live in the parish where they are listed. Their land may have stretched into a neighbouring parish.

- Before printed returns came into use in 1798, the layout and content of assessments can be highly idiosyncratic. Clerks occasionally failed to put a heading to the columns of names and figures, or reversed the usual order of them.

Where to find them

The land tax assessments for Norfolk are preserved amongst the Norfolk Quarter Sessions records. These are held on microfiche at the Norfolk Record Office at the Archive Centre, County Hall, and at the Norfolk Heritage Centre at the Norfolk and Norwich Millennium Library. They are arranged by divisions (or hundreds) and are in annual bundles for each division from 1767 to 1832. The catalogue reference for the documents is C/Scd 2. Staff at the archive and heritage centres will be able to assist with locating the microfiches for your parish. Please note returns do not survive for every parish for the whole of this period.